Sharp-tailed grouse

| Sharp-tailed grouse | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Genus: | Tympanuchus |

| Species: | T. phasianellus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tympanuchus phasianellus | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

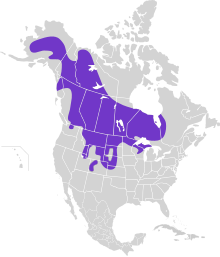

The sharp-tailed grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus), also known as the sharptail or fire grouse, is a medium-sized prairie grouse. One of three species in the genus Tympanuchus, the prairie chickens. the sharp-tailed grouse is found throughout Alaska, much of Northern and Western Canada, and parts of the Western and Midwestern United States. The sharp-tailed grouse is the provincial bird of the Canadian province of Saskatchewan.[2]

Taxonomy

[edit]In 1750 the English naturalist George Edwards included an illustration and a description of the sharp-tailed grouse in the third volume of his A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. He used the English name "The Long-tailed Grous from Hudson's-Bay". Edwards based his hand-coloured etching on a preserved specimen that had been brought to London from Hudson Bay by James Isham.[3] When in 1758 the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus updated his Systema Naturae for the tenth edition, he placed the sharp-tailed grouse with other grouse in the genus Tetrao. Linnaeus included a brief description, coined the binomial name Tetrao phasianellus and cited Edwards' work.[4] The sharp-tailed grouse is now placed in the genus Tympanuchus that was introduced in 1841 by the German zoologist Constantin Wilhelm Lambert Gloger for the greater prairie chicken.[5][6] The genus name combines the Ancient Greek tumpanon meaning "kettle-drum" with ēkheō meaning "to sound". The specific epithet phasianellus is a diminutive of the Latin phasianus meaning "pheasant".[7]

The greater prairie chicken, lesser prairie chicken, and sharp-tailed grouse make up the genus Tympanuchus, a genus of grouse found only in North America. Six extant and one extinct subspecies of sharp-tailed grouse are recognised:[8][6]

- T. p. phasianellus: the nominate race or northern sharp-tailed grouse is found in Manitoba, northern Ontario, and central Quebec. It is partly migratory.

- T. p. kennicotti: the northwestern sharp-tailed grouse is resident from the Mackenzie River to the Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories, Canada.

- T. p. caurus: the Alaskan sharp-tailed grouse inhabits north-central Alaska eastwards to the southern Yukon, northern British Columbia, and northern Alberta.

- T. p. columbianus: the Columbian sharp-tailed grouse can be found in isolated pockets of native sagebrush and bunchgrass plains of Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and British Columbia.

- T. p. campestris: the prairie sharp-tailed grouse lives in Saskatchewan, southeastern Manitoba, southwestern Ontario, and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to northern Minnesota and northern Wisconsin. This subspecies coexists with the plains race around the northern Red River Valley and prefers low seral stages of recently converted forests to shrubland.

- T. p. jamesi: the plains sharp-tailed grouse makes its home in the northern Great Plains in southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, eastern Montana, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, and northeastern Wyoming. This race lives in the mixed-grass prairie, preferring a mosaic of native grasslands, cropland, and brushy/woody riparian draws, creeks, and rivers for a winter food source above the snow cover as buds and berries.

- †T. p. hueyi: the New Mexico sharp-tailed grouse is extinct.

Description

[edit]

Adults have a relatively short tail with the two central (deck) feathers being square-tipped and somewhat longer than their lighter, outer tail feathers giving the bird its distinctive name. The plumage is mottled dark and light browns against a white background, they are lighter on the underparts with a white belly uniformly covered in faint V-shaped markings. These markings distinguish sharp-tailed grouse from lesser and greater prairie chickens which are heavily barred on their underparts.[9] Adult males have a yellow comb over their eyes and a violet display patch on their neck. This display patch is another distinguishing characteristic from prairie chickens as male prairie chickens have yellow or orange colored air sacs.[9] The female is smaller than the male and can be distinguished by the regular horizontal markings across the deck feathers as opposed to the irregular markings on the males deck feathers which run parallel to the feather shaft. Females also tend to have less obvious combs.

Measurements:[10]

- Length: 15.0-19.0 in (38.1-48.3 cm)

- Weight: 21.0-31.0 oz (596-880 g)

- Wingspan: 24.4-25.6 in (62-65 cm)

Distribution

[edit]Sharp-tailed grouse historically occupied eight Canadian provinces and 21 U.S. states pre-European settlement.[11] They ranged from as far north as Alaska, south to California and New Mexico, and east to Quebec, Canada.[11] Following European settlement the sharp-tailed grouse has been extirpated from California, Kansas, Illinois, Iowa, Nevada, and New Mexico.[12][9]

Behavior

[edit]

Feeding

[edit]These birds forage on the ground in summer, in trees in winter. They eat seeds, buds, berries, forbs, and leaves, also insects, especially grasshoppers, in summer. Specific species of grasshopper the sharp-tailed grouse is known to feed on are Melanoplus dawsoni and Pseudochorthippus curtipennis.[13]

Breeding

[edit]The sharp-tailed grouse is a lekking bird species. These birds display in open areas known as leks with other males, anywhere from a single male to upwards of 20 will occupy one lek (averaging 8-12). A lek is an assembly area where animals carry on display and courtship behavior. During the spring, male sharp-tailed grouse attend these leks from March through July with peak attendance in late April, early May.[9] These dates do fluctuate from year to year based on the weather. Johnsgard (2002) observed weather delayed lekking of up to two weeks by sharp-tailed grouse in North Dakota. The males display on the lek by stamping their feet rapidly, about 20 times per second, and rattle their tail feathers while turning in circles or dancing forward. Purple neck sacs are inflated and deflated during display. The males use "cooing" calls also to attract and compete for females.[14][15][9] The females select the most dominant one or two males in the center of the lek, copulate, and then leave to nest and raise the young in solitary from the male. Occasionally a low-ranking male may act like a female, approach the dominant male and fight him.

Habitat selection

[edit]The sharp-tailed grouse is found throughout different prairie ecosystems in North America. They inhabit ecosystems from the pine savannahs of the eastern upper Midwest to the short grass, mid grass, and shrub steppe prairies of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain West.[11][12][16] Selection of specific habitat characteristics and vegetation communities is variable among the different subspecies of sharp-tailed grouse. Selection of these specific habitats depends on the quality of habitat available to grouse.[17][18][19][20][12] The major habitats used by sharp-tailed grouse, recorded in the literature, are savannah style prairie with grasses dominant and shrub patches mixed throughout, with minimal patches of trees.[21][22][23][17][11] In fact, Hammerstrom (1963) states the taller the woody vegetation, the less of it there should be in the habitat. The savannah style habitat is mostly preferred during the summer and brood rearing months through autumn. This general habitat is used during all four seasons for different features. Habitat selection and usage vary by season with; lekking, nesting, brood rearing, and winter habitat selected and utilized differently.

Lekking habitat

[edit]The lek, or dancing ground is, usually made up of short, relatively flat native vegetation.[24][25] Other habitat types utilized for leks are cultivated lands, recent burns, mowed sites, grazed hill tops, and wet meadows.[26][27][12][11] Manske and Barker (1987) reported sun sedge (Carex inops), needle and thread grass (Hesperostipa comata), and blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) on lekking grounds in the Sheyenne National Grassland in North Dakota. The males also select for upland or midland habitat type on the tops of ridges or hills.[25] Leks surrounded by high residual vegetation were observed by Kirsch et al. (1973). They noticed lek distribution was influenced by the amount of tall residual vegetation adjacent to the lek. Lek sites eventually became abandoned if vegetation structure was allowed to get too high. The invasion of woody vegetation and trees into lekking arenas also caused displaying males to abandon leks.[21][19] Moyles (1981) observed an inverse relationship of lek attendance by males with an increase in quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) within 0.8 km of arenas in the Alberta parklands. Berger and Baydack (1992) also observed a similar trend in aspen encroachment where 50% (7 of 14) of leks were abandoned when aspen coverage increased to over 56 percent of the total area within 1 km of the lek. Males select hilltops, ridges, or any place with a good field of view for leks. So they can see the surrounding displaying males, approaching females to the dancing ground, and predators.[11][14][25]

Nesting habitat

[edit]Nesting cover is one of the most important habitat types needed by sharp-tailed grouse hens. Nesting habitat varies widely among the different subspecies of sharp-tailed grouse.[18] Hamerstrom Jr. (1939) found the majority of prairie sharp-tailed grouse (T. p. campestris) nests occupied dense brush and woods at marsh edges. Gieson and Connelly (1993) reported that Columbian sharp-tailed grouse (T. p. columbianus) selected for dense shrub stands with taller, denser shrubs located at the nest site. Plains sharp-tailed grouse (T. p. jamesii) selected nest sites with dense residual vegetation and a shrubby component.[18] However, nest sites are usually characterized by dense tall residual vegetation (last year’s growth) with the presence of woody vegetation either at the nest site or nearby.[25][28] Goddard et al. (2009) state that the use of shrub dominated habitats has not been documented by many other researchers. Goddard et al. (2009) found that sharp-tailed grouse hens in Alberta, Canada selected more for shrub steppe habitats in their first nest attempts because of increased concealment provided by the shrubs than the residual grass earlier in the breeding season. Roersma (2001) also found that grouse in southern Alberta selected taller, woody vegetation compared to all other habitats assessed, and grouse used this area in greater proportions to available woody habitat. These findings contradict Prose et al. (2002), who states that residual vegetation is critical to sharp-tailed grouse nest success due to the early seasonal nesting nature of the grouse.

Brood habitat

[edit]Sharp-tailed grouse are a precocial species, meaning that they hatch with their eyes open, are self-reliant, and do not require the mother to feed them. Shortly after hatching, the chicks and mother leave the nest site in search of cover and food. Brood rearing habitats of sharp-tailed grouse have many characteristics including: shrubby vegetation for concealment, short vegetation nearby for feeding, and high amounts of forbs present.[22][20][25][18][17] This could explain why sharp-tailed grouse nest in or close to shrub communities. The shrub component in brooding habitat provides good canopy protection from direct sunlight and avian predators.[18][17] Hamerstrom (1963) and Goddard et al. (2009) both observed the greatest number of sharp-tailed grouse broods present in open, rather than wooded landscapes. Both hypothesized this use of open landscape was due to an abundance of insects for the chicks and green herbaceous cover for the hen to feed on. Habitat usage by sharp-tailed grouse broods is a function of time of day, available habitat, and weather.[26][20] Brood habitats are made up of many complex habitat types. Broods may utilize shrubby areas or oak grassland savannah type habitats.[22] Broods utilize these types of habitats for cover, while remaining close to prime foraging habitats in the form of shorter vegetation with a mixture of native vegetation.

Winter habitat

[edit]Winter habitat usage by sharp-tailed grouse seems to shift toward denser cover for thermal insulation. Hammerstrom and Hammerstrom (1951) noticed that grouse use thicker edge type habitat more than the open ground during the winter in Michigan and Wisconsin. Hammerstrom and Hammerstrom (1951) also noted that birds, when found in open habitat, were no more than a few hundred meters from thicker cover. These birds were usually utilizing grain fields. Swenson (1985) observed the same trend in Montana. Hamerstrom and Hammerstrom (1951) declared that use of forested habitat by sharp-tailed grouse vary by location, noting that sharp-tailed grouse in more semi-arid and arid areas utilize brush less frequently in winter. However, Hammerstrom and Hammerstrom (1951) did report that sharp-tailed grouse in Washington and California were observed using edge type habitats more frequently during winter months. Manske and Barker (1987) noticed a similar trend in winter habitat usage in North Dakota, noting that sharp-tailed grouse in small flocks joined together to form larger packs in severe weather. These packs move from open prairie, to shelterbelts, and adjacent croplands with standing corn and sunflowers. Habitat usage in winter varies greatly as a function of snow depth (Swenson 1985). As snow depth increases, habitat selection shifts from cropland and prairie to shelterbelts and woody vegetation. One habitat change seen by Hamerstrom and Hamerstrom (1951), was grouse would select large snow banks to burrow into, to keep warm during cold nights. The use of burrows was also noted by Gratson (1988).

Habitat fragmentation

[edit]Habitat fragmentation has been one of factors driving the decline of all subspecies of sharp-tailed grouse across its entire range throughout North America.[29] The type of habitat fragmentation varies from ecological succession, as shrub/grassland areas transition into forested areas. Fire suppression, tree plantings, limiting logging practices, and an increase of invasive woody species have also led to habitat fragmentation. The largest contributor to habitat fragmentation has been the agriculture industry.

The Homestead Act 1862 opened up great expanses of virgin prairie in the west to early settlers. By 1905 about 41 million hectares of the west had been homesteaded.[30] Much of this land was in semi-arid rangelands with sub-marginal precipitation to support crop production.[30] The plowing of this land represented a permanent change in the nature of the land. Another contributor to habitat fragmentation for grouse is unmonitored and excessive cattle grazing.[31][32][33] Cattle can be an important tool to manage habitat structure for sharp-tailed grouse when managed properly (Evens 1968). The habitat of sharp-tailed grouse was severely affected by early settlers before cattle grazers understood the impact to the environment from overgrazing.

A secondary effect of early agriculture during the years of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression in the late 1920s and early 1930s was when homesteaders abandoned the unproductive land.[30] The United States government bought up much of this land through the Land Utilization Program, with management eventually controlled by the United States Forest service and the Bureau of Land Management.[34][30] During the drought years of the 1930s, these agencies re-vegetated some of these areas with non-native highly competitive vegetation such as smooth brome (Bromus inermis) and crested wheatgrass (Agropyron cristatum).[35] These plants served their purpose by re-vegetating and protecting the soil. But these invaders became great competitors and directly affected native vegetation. In some instances crested wheatgrass and smooth brome have forced out native vegetation, creating monoculture habitats. Monoculture habitats are not favored by sharp-tailed grouse, as they prefer sites with high heterogeneity. Hamerstrom (1939) was quoted as saying "More important than the individual cover plants is the fact that most of the nests of all species were in cover mixtures rather than pure stands."

Habitat assessment

[edit]Research conducted before 1950 on sharp-tailed grouse habitat assessment was done visually. Hamerstrom (1939) reported sparse vegetation was seldom selected for nesting due to lack of adequate cover. Habitat generalizations were formed based on the number of individuals found at a given local. These assumptions were if more birds were present at one location and less at another, then the first must be the better habitat. Hamerstrom (1963) observed 119 of 207 (57%) grouse broods frequenting savannah style habitat. He concluded that the savannah style habitat was the habitat needed for best management. As the research on habitat for grouse species matured, so did the techniques used for assessment. Cover boards and Robel poles were developed to measure visual obstruction (VO) and create habitat indices. Cover boards were developed as early as 1938 by Wight (1938) to study white-tailed deer habitat. Wight’s (1938) cover board was 6 feet in height, marked and numbered every foot. Visible marks were counted to measure obstruction by plants. Kobriger (1965) developed a 4×4-foot board marked at 3-inch intervals with alternating white and black squares. He placed a camera in the center of the breeding ground at a height of 3 feet. He then placed the cover board 30 feet away taking photographs of the cover board. After compiling all the photographs, they were analyzed with a hand lens to assess the number of squares visible. This number gave him a vegetation index of cover classes. This method has been modified by Limb et al. (2007). Instead of taking photographs 30 feet away like Kobriger (1965), Limb et al. (2007) took photographs of vegetation back-dropped by a 1×1-meter cover board at a height of 1 meter, 4 meters away. These digital photographs were uploaded to Adobe Acrobat and digitized to the 1×1-meter backdrop.[36] Robel et al. (1970) developed a pole to determine height based on correlated vegetation weight. The pole was duly named the Robel pole. Robel et al. (1970) found that VO measurements taken at a height of 1 m and a distance of 4 m from the pole gave a reliable index of the amount of vegetation production at a location. Hamerstrom et al. (1957) were quoted as saying "Height and density of grass were clearly more important to the prairie chickens than species composition" as reported by Robel et al. (1970). This was also believed to be true for the sharp-tailed grouse. These key aspects can now be assessed using the Robel pole, Nudds cover board, and Limb et al. digital photography method effectively and efficiently.

Management

[edit]It is apparent that the effects of habitat fragmentation across all habitat types selected by sharp-tailed grouse are impacting this species. The management of sharp-tailed grouse habitat has changed over the years from observational (making sure current habitat is maintained) to a more hands on approach. The management of lekking habitat and winter habitat are not as clearly defined in the literature as nesting and brood rearing habitat assessment and management. The development of the Robel pole and cover boards has become a key tool in habitat assessment providing land managers a means to inventory and study habitat preferences based on vegetation structure and density. The Robel pole has become the more favored of the two methods in recent years for habitat assessment. The United States Forest Service (USFS) uses visual obstruction readings (VOR) to set stocking densities for cattle based on the current years standing residual vegetation . This method is currently conducted on the USFS Little Missouri Grasslands, Cheyenne National Grasslands, Cedar River National Grassland, and Grand River National Grassland, all found in the Dakota Prairie National Grasslands in North and South Dakota.[35]

The Robel pole is a non-destructive method for inventorying vegetative biomass.[37][38] This method was used to create a habitat suitability index based on vegetation visual obstruction (VO), ranging from 0-30.5 cm with a suitability index rating of 0-1.0.[39] Studies of nesting habitat by Prose et al. (2002) in the Nebraska Sandhills found that nesting sharp-tailed grouse selected nest sites with visual obstruction readings (VOR) of more than 4 cm. Similarly, Clawson and Rottella (1998) observed that 58% of nests (432 of 741) in Southwestern Montana were located in sites with an average VOR of 24 cm. The other nests in this study were located in sites with VOR’s of 11–18 cm. Reece et al. (2001) observed that sites with a VO of less than 5 cm near possible nesting locations indicated a decline in quality nesting habitat as average VO declined. The use of the Robel pole to assess habitat for sharp-tailed grouse has given managers a target height of vegetation structure to have at the end of the grazing season. This allows managers to set the appropriate stocking rate to best attain a desired vegetation height. As a rule of thumb, the average VOR reading for suitable grouse nesting habitat is 3.5in (8.89 cm). Lekking habitat can be managed by burning, mowing, clear cutting, and grazing across the entire range of the sharp-tailed grouse subspecies. Ammann (1957) found that leks that contained woody vegetation did not exceed 30% of the total lek area. Similarly, Moyles (1989) found a negative correlation with increased in aspen trees (Populus tremuloides) on lekking sites and the number of displaying males present. Trees may provide perches for avian predators but further work needs to be done on the effects of woody plant encroachment.

Status and conservation

[edit]These birds are increasing in numbers and are listed as least concern.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International. (2021). "Tympanuchus phasianellus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T22679511A138099395. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22679511A138099395.en.

- ^ Government of Saskatchewan. "Emblems of Saskatchewan". Archived from the original on 2017-06-19. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ^ Edwards, George (1750). A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Vol. Part III. London: Printed for the author at the College of Physicians. p. 117, Plate 117.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 160.

- ^ Gloger, Constantin Wilhelm Lambert (1841). Gemeinnütziges Hand- und Hilfsbuch der Naturgeschichte (in German). Vol. 1. Breslau: A. Schulz. p. 396.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Pheasants, partridges, francolins". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 393, 302. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Hoffman et al. (2007), p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e Connelly, J. W.; Gratson, M. W.; Reese, K. P. (1998-01-01). "Sharp-tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus)". The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.354.

- ^ "Sharp-tailed Grouse Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ a b c d e f Johnsgard, P.A. (2002.) Dawn Dancers on Dun Grass The sharp-tailed Grouse and the Northern Prairies and Shrublands. Pages 81–103 in Grassland Grouse. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington and London.

- ^ a b c d Johnsgard, P.A. 1973. Sharp-tailed Grouse. pp. 300–319 in Grouse and Quails of North America. The University of Nebraska Lincoln press.

- ^ Meyhoff, Sejer D.; Johnson, Daniel L.; Bazinet, Scott (September 2020). "Fall diet in sharp-tailed grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus jamesi) and consumption of the grasshopper Melanoplus dawsoni in Alberta, Canada". Food Webs. 24: e00153. Bibcode:2020FWebs..2400153M. doi:10.1016/j.fooweb.2020.e00153. S2CID 225295442.

- ^ a b Sisson, L. 1969. Land Use Changes and Sharp-Tailed Grouse Breeding Behavior Nebraska Game and Parks Commission White Papers, Conference Presentations, & Manuscripts.

- ^ "Adaptive Strategies and Population Ecology of Northern Grouse. Arthur T. Bergerud , Michael W. Gratson". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 63 (4): 479. 1988-12-01. doi:10.1086/416091. ISSN 0033-5770.

- ^ Aldrich, J.W. 1963. Geographic orientation of American Tetraonidae. Journal of Wildlife Management 27: 529-545.

- ^ a b c d Goddard, A. D.; R. D. Dawson; M.P. Gillingham. 2009. Habitat selection by nesting and brood-rearing sharp-tailedgrouse. Canadian Journal of Zoology, Apr2009, Vol. 87 Issue 4, p326-336, 10p, 6 charts, 2 graphs; doi:10.1139/Z09-016; (AN 37580857)

- ^ a b c d e Roersma, S.J. 2001. Nesting and brood rearing ecology of plains sharp-tailed grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus jamesi) in a mixed-grass/fescue ecoregion of Southern Alberta. M.Sc. thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg.

- ^ a b Swenson, J. E. 1985. Seasonal habitat use by sharp- tailed grouse, Tympanuchus phasianellus, on mixed-grass prairie in Montana. Can. Field-Nat. 99:40-46. YOCOM, C. F. 1952.

- ^ a b c Kohn, S. C. 1976. Sharp-tailed grouse nesting and brooding habitat in southwestern North Dakota, North Dakota Game and Fish Department.

- ^ a b Moyles, DLJ. 1981. Seasonal and Daily Use of Plant Communities by Sharp-Tailed Grouse (Pedioecetes phasianellus ) in the Parklands of Alberta. Canadian field-naturalist. Ottawa ON Vol. 95, no. 3, pp. 287–291.

- ^ a b c Hamerstrom Jr, F. N. 1963.Sharptail Brood Habitats in Wisconsin’s Northern Pine Barrens. The Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 27, No. 4. 793-802.

- ^ Robel, R. J., R.F. Henderson, and W. Jackson. 1972. Some Sharp-Tailed Grouse PopulationStatistics from South Dakota. The Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Jan., 1972), pp. 87–98.

- ^ Hanowski, JAM, D.P. Christian, and G.J. Niemi. 2000. Landscape requirements of prairie sharp- tailed grouse Tympanuchus phasianellus campestris in Minnesota, USA. Wildlife Biology Vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 257–263.

- ^ a b c d e Manske, L. L.; W. T. Barker. 1987. Habitat Usage by prairie grouse on the Sheyenne National Grasslands. pp. 8–20. In: A. J. Bjugstad, tech. coord. Prairie Chickens on the Sheyenne National Grasslands. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-159. Fort Collins, CO: U. S. Department of Agriculture, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

- ^ a b Ammann, G.A. 1957. The prairie grouse of Michigan. Michigan Department of Conservation technical bulletin.

- ^ Kobriger, G. D. 1965. Status, Movements, Habitats, and Foods of Prairie Grouse on a Sandhills Refuge. The Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Oct., 1965), pp. 788–800.

- ^ Prose, B.L., B.S. Cade, and D. Hein. 2002. Selection of nesting habitat by sharp-tailed grouse in the Nebraska sandhills. Prairie Naturalist. 34(3/4):85-105.

- ^ Silvy, Nova J.; Hagen, Christian A. (2004-03-01). "Introduction: Management of imperiled prairie grouse species and their habitat". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 32 (1): 2–5. doi:10.2193/0091-7648(2004)32[2:IMOIPG]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7648. S2CID 86022197.

- ^ a b c d Olsen, E. 1997. National Grassland Management A Primer. Natural Resource Division Office of the General Council USDA. pp. 1–40.

- ^ Giesen, K. M. and J.W. Connelly. 1993. Guidelines for Management of Columbian Sharp-Tailed Grouse Habitats. Wildlife Society Bulletin, Vol. 21 Issue 3, p325-333.

- ^ Kirsch, L. M., A.T. Klett, and H. W. Miller. 1973. Land Use and Prairie Grouse Population Relationships in North Dakota. The Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Oct., 1973), pp. 449–453.

- ^ Reece, P.E., J.D. Volesky, and W.H. Schacht. 2001. Cover for Wildlife after Summer Grazing on Sandhills Rangeland. Journal of Range Management. Vol. 54, No. 2 pp. 126–131.

- ^ Wooten, H. H. "The Land Utilization Program 1934 to 1964 Origin, Development, and Present Status," in Appendix C of National Grassland Management Primer (1965).

- ^ a b USFS land management plan for the Dakota Prairie Grasslands Northern Region 2001.

- ^ Limb, R.F., K.R.Hickman, D.M. Engle, J.E. Norland, and S.D. Fuhlendorf. 2007. Digital photography: Reduces investigator variation in visual obstruction measurements for southern tallgrass prairie. Range land Ecology Management. 60: pp. 548–552.

- ^ Robel, RJ., J.N. Briggs, A.D. Dayton, and L.C. Hulbert. 1970. Relationships between visual obstruction measurements and weight of grassland vegetation. Journal of Range Management. 23:295-297.

- ^ Benkobi, L., D.W. Uresk, G. Schenbeck, and R. M. King. 2000. Protocol for Monitoring Standing Crop in Grasslands Using Visual Obstruction. Journal of Range Management, Vol. 53, No. 6, pp. 627–633

- ^ Prose, B.L. (1987): Habitat suitability index models: plains sharp-tailed grouse. U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv. Biol. Rep. 82: 10.142. 31 pp. PDF fulltext

Further reading

[edit]- Berger, R.P., and R.K. Baydack. 1992 Effects of aspen succession on sharp-tailed grouse, Tympanuchus phasianellus. In the interlake region of Manitoba. Canadian Field naturalist 106: 185-191

- Bergerud, A. T. 1988. Mating Systems in Grouse. Pages 439-470 in Adaptive strategies and population ecology of northern grouse. (Bergerud, A. T. and M. W. Gratson, Eds.) Univ. of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- Bergerud, A. T. and M. W. Gratson 1988. Population ecology of North American grouse. Pages 578-685 in Adaptive strategies and population ecology of northern grouse. (Bergerud, A. T. and M. W. Gratson, Eds.) Univ. of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

- Clarke, Julia A. (2004): Morphology, Phylogenetic Taxonomy, and Systematics of Ichthyornis and Apatornis (Avialae: Ornithurae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 286: 1-179 PDF fulltext

- Clawson, M.R., and J.J. Rotella. 1998. Success of Artificial Nests in CRP Fields, Native Vegetation, and Field Borders in Southwestern Montana. Journal of Field Ornithology, Vol. 69, No. 2 pp. 180–191

- Connelly, J. W., M. W. Gratson and K. P. Reese. 1998. Sharp-tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/354

- Conover, M. R., and J.S. Borgo. 2009. Do Sharp-Tailed Grouse Select Loafing Sites to Avoid Visual or Olfactory Predators? Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 73, No. 2, pp. 242–247

- Giesen, K. M. and J.W. Connelly. 1993. Guidelines for Management of Columbian Sharp-Tailed Grouse Habitats. Wildlife Society Bulletin, Vol. 21 Issue 3, p325-333

- Gratson, M. W. 1988. Spatial patterns, movements, and cover selection by Sharp-tailed Grouse. Pages 158-192 in Adaptive strategies and population ecology of northern grouse. (Bergerud, A. T. and M. W. Gratson, Eds.) Univ. of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

- Hamerstrom Jr, F. N., and F. Hamerstrom. 1951. Mobility of the Sharp-Tailed Grouse in Relation to its Ecology and Distribution. American Midland Naturalist. Vol. 46, No. 1 (Jul., 1951), pp. 174–226 Published by: The University of Notre Dame

- Henderson, F. R., F. W. Brooks, R. E. Wood, and R. B. Dahlgren. 1967. Sexing of prairie grouse by crown feather patterns. Journal of Wildlife Management. 31:764-769.

- Hoffman, R.W.; & Thomas, A.E. (17 August 2007): Columbian Sharp-tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus columbianus): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. 132 pp. PDF fulltext Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- Johnsgard, P.A.2002. Dawn Dancers on Dun Grass The sharp-tailed Grouse and the Northern Prairies and Shrublands. Pages 81–103 in Grassland Grouse. (Johnsgard, P.A.) Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington and London

- Jones, R. E. 1968. A Board to Measure Cover Used by Prairie Grouse. The Journal of WildlifeManagement, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 28–31

- Moyles, DLJ. 1981. Seasonal and Daily Use of Plant Communities by Sharp-Tailed Grouse (Pedioecetes phasianellus ) in the Parklands of Alberta. Canadian field-naturalist. Ottawa ON Vol. 95, no. 3, pp. 287–291.

- Nudds, T. D. 1977. Quantifying the Vegetative Structure of Wildlife Cover. Wildlife Society Bulletin. Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 113–117

- Olsen, E. 1997. National Grassland Management A Primer. Natural Resource Division Office of the General Council USDA. pp. 1–40

- Prose, B.L. (1987): Habitat suitability index models: plains sharp-tailed grouse. U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv. Biol. Rep. 82: 10.142. 31 pp. PDF fulltext

- Prose, B.L., B.S. Cade, and D. Hein. 2002. Selection of nesting habitat by sharp-tailed grouse in the Nebraska sandhills. Prairie Naturalist. 34(3/4):85-105.

- Swenson, J. E. 1985. Seasonal habitat use by sharp- tailed grouse, Tympanuchus phasianellus, on mixed-grass prairie in Montana. Can. Field-Nat. 99:40-46. YOCOM, C. F. 1952.

- Wight, H.M. 1938. Field and laboratory techniques in wildlife management. Univ. of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. 108pp.

External links

[edit] Media related to Tympanuchus phasianellus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tympanuchus phasianellus at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Tympanuchus phasianellus at Wikispecies

Data related to Tympanuchus phasianellus at Wikispecies- Sharp-tailed grouse fighting in super slow motion video from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Sharp-tailed Grous(sic) by John James Audubon Hi-resolution close-ups from Birds of America

- Sharp-tailed Grouse Species Account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Sharp-tailed Grouse Tympanuchus phasianellus - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter